Havana, Cuba. December 31st, 1960. Celebrations were quieter since the revolution. Whether out of exhaustion or fear, Clara and Eduardo insisted on welcoming the New Year without mentioning politics. The young couple ran through family gossip and softly chuckled about their youngest son’s mischief as they finished the dinner preparations. Jorge Victor, a friend who had also taken part in the counter-revolutionary campaign, joined the family in the small apartment of El Vedado, near Old Havana.

As the trio set on their main dish, the front door suddenly toppled to the ground to reveal three men of the revolutionary militia— rifles in hand, crackling cigarettes in mouth, rosaries bound around their necks. They ravaged the apartment, searching for anything that might give the 24-year-olds away as dissidents. Though finding nothing, they assassinated Jorge Víctor on the spot.

The young couple had just enough time to pack one suitcase and grab the ten dollars hidden in the cupboard before scurrying to a friend’s home with their children. They fled to Venezuela just a week later—never to return to the island. The morning of January 1st, 1961, Jorge Víctor greeted the New Year alone. He lay flat on his back. His open eyes glared at Cuba’s future under Fidel Castro.

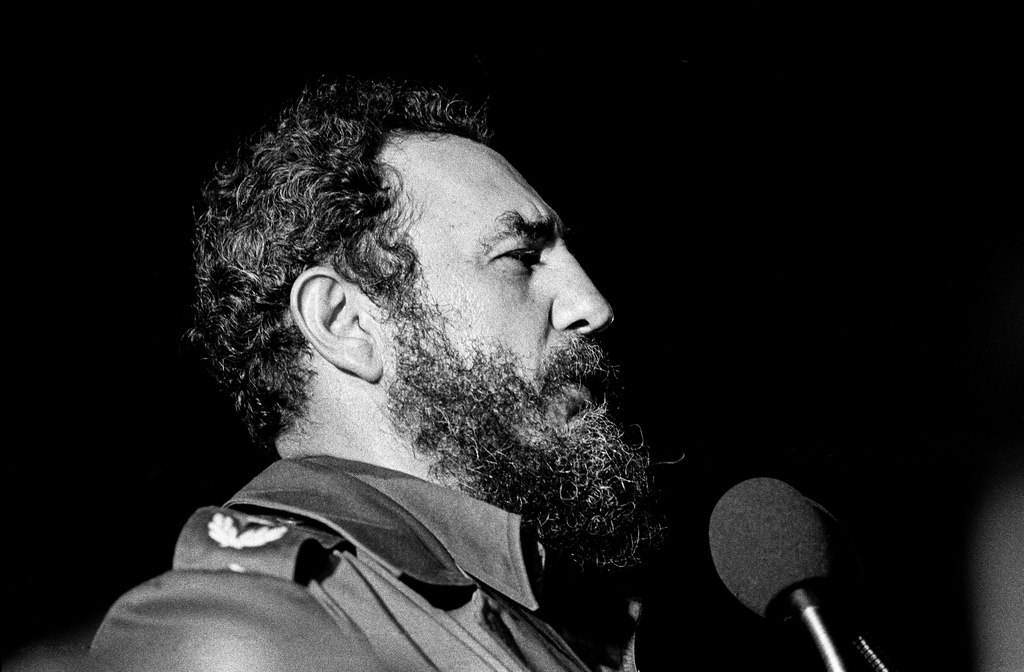

To some, the silhouette of the scruffy beard, half-smoked cigar and guerrilla beret is a symbol of a romantic hero of the Cold War, who liberated Cuba from a U.S.-backed dictatorship. To others, it is nothing more than the costume worn by a hollow patriot, who promised the Cuban people liberation, and instead bound them within a prison of destitution.

Dubbed El Comandante by supporters, Fidel Castro overthrew President Fulgencio Batista in a coup in 1959 and soon after proclaimed the island to be the communist “pearl of the Caribbean.” In the famous speech that ran over four hours in 1953, Castro divined that history would absolve him for his sins in the struggle for Cuba’s liberation.

Fidel Castro’s legacy will surely be as contradictory as his 60 years in power, and with his death on November 25, 2016, the extremes have resurfaced: Amid the nostalgic portrayals of a hero in the media and tributes from leaders in the international community, there were sketches of a monster described by Cuban exiles who rejoiced in his passing.

International leaders’ responses upon his death reinforce his prophecy of exoneration. “The world has lost a man who was a hero,” wrote Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the EU Commission.

“I join the people of Cuba in mourning the loss of this remarkable leader,” added Canada’s young PM, Justin Trudeau.

“For all his flaws, Castro was a champion of social justice,” chimed in Jeremy Corbyn, Leader of the Labour Party in the UK.

Even the mainstream media have been seduced by the allure of a romanticized Castro. The BBC, for example, painted his controversial reign as natural. In its obituary to the revolutionary, it hailed him as “one of the world’s longest-serving leaders.” That he was the longest-serving leader due to an entirely undemocratic regime seemed to be a mere parenthesis in a greater tale of revolution and liberation for the Cuban people, who were bestowed with an education and healthcare system unmatched in the world today.

Yet history should not absolve Castro so easily.

Often painted as a prophet of education and healthcare for the Cubans, the revolutionary leader did achieve impressive results with the Cuban literacy rate at roughly 99%, according to the World Bank, compared with the average of 51% in developing countries.

Yet those soaring literacy rates are met with a society too poor to purchase books and even basic goods. Breakdowns in production have caused severe food shortages over decades and have led to average monthly earnings per person of 20 USD, according to the National Review.

Castro is also credited with providing free universal healthcare to the Cuban people. “They’ve become known as having not only one of the best healthcare systems, but as being one of the most generous in providing doctors and medical equipment to third-world countries,” said Michael Moore in Sicko, his 2007 documentary that featured Americans who traveled to the island to receive free treatment.

The regime, however, excludes its own people from this medical paradise. In one Havana hospital, the PanAm Post reported biological waste hanging in a regular trash bin, beds without linen, and a bag of IV fluids hanging above the patients as the only equipment around. “Well, they have to bring everything with them, because the hospital provides nothing. Pillows, sheets, medicine: everything,” said the Post’s guide.

For all his words of liberation, Castro’s reign resulted in the imprisonment of his own people. According to the Cuba Archive, his government has overseen some 4,000 firing squad executions and over 1,200 extra-judicial killings. Human Rights Watch reports more than 6,200 reports of arbitrary detentions in 2015 alone – a statistic from the Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation, an independent human rights group that the government views as illegal

And Article 216 of Cuba’s Penal Code forbids Cuban citizens from leaving the island without prior government authorization and penalizes attempts with years imprisonment.The tens of thousands of lives lost fleeing the island, whether on the seas by the valseros (rafters) or other crafts – an estimated 78,000 – bear witness to the Cuban will to liberty despite the repercussions.

As with all authoritarians, Castro was a paradox in his lifetime. And in death, he will likely remain so, unless the international community and media ensure that his prophecy of exoneration remains unfulfilled.

Little Havana, Miami, December 31st 2016:

After 10 years in Florida, Cuban exile Clara’s feelings are complicated:

“I refuse to partake in the revelry of the many Miamians who have crowded to the streets to rejoice and sing the Guantanamera,” she said. “But I also refuse to stay silent on the media’s and world leaders’ gross mischaracterizations of this excuse of a patriot.”

Clara and Eduardo have now lived through 60 years of marriage and have raised seven children. After exiles from Cuba and Venezuela, the couple now makes Old Havana, Miami, their final home. But Clara misses Cuba.

“When I close my eyes and inhale deeply, I can again breathe in the breeze of the Malecón. The air is vibrant, but not yet fresh. It will take time to cleanse it, as it has taken time to pollute it over decades of grief,” she said. “And if I’m unable to do so, you and your generation will have to breathe it in for me – that curative, humid breeze saturated by history.”

For somebody that has directly suffered the pain of Castro’s rule – living in exile, mourning relatives’ deaths by execution or fatal attempts at fleeing – her prescription is humbling: Neither revile, blinded by emotions, nor eulogize, blind to history.

Rather, she says, let us reconcile with an eye, for once, to the future and to the good of the Cuban people.

In this project, Fidel Castro is likely to be an afterthought.